A political party based on anti-immigrant sentiment. Neighbors taking sides against each other over civil rights, political expression and the fear that their ways of life were changing for the worse. Newspapers accused of publishing fake news, stirring people into violence. This was 163 years ago in Louisville. It could be now... or could it?

______________________________________

A woman with a baby clinging to her neck emerges from a burning row house in a small part of Louisville known as Quinn’s Row and into the street. Her home, on West Main Street in downtown Louisville, has been set ablaze by rioters. Several of her neighbors lie dead in the street.She staggers forth, but all around she sees fire and violence — seemingly every house in the block, between 10th and 11th streets is burning. The woman, dragging bedding she salvaged from her now-engulfed home, is kicked by one of the rioters and her bedding snatched away and set on fire. The man kicking her derides, shouting, “We will learn you that Americans rule America!”

Her crime?

She is an Irish immigrant and a Catholic.

That eye-witness account was published by an Indianapolis newspaper in the days following the Aug. 6, 1855 uprising that is now known as the Bloody Monday riots. The tumult in the early morning of that Louisville Election Day left at least 22 people dead, dozens of homes and businesses burned down or damaged and many other homes, stores and businesses looted.

The riots are largely forgotten in Louisville today. It took until 2006 for a historical marker to be erected in the block where that Irish woman was brutalized, people were killed and homes burned. Bloody Monday happened due to a paranoid wave of nationalist thinking that led to anti-immigrant aggression. It involved religious bias and fear. It involved biased media stoking the fires of already mounting tension with what essentially was 19th-century “fake news.”

At the time, Louisville’s population was about 43,000, with roughly a third recently-settled immigrants from Ireland and Germany. This alone had native-born Protestants feeling as though their city was being taken over, as the newcomers were politically active yet were loathe to change their homeland traditions. In addition, the German population in particular supported issues such women’s suffrage and the abolition of slavery, which didn’t sit well with the native-born Americans.

Following the riots, hundreds, or even thousands, of the immigrants would flee the city. Since then, of course, thousands of immigrants have come to Louisville from around the world, leaving the city much more diverse. But given the current political climate, it would be wise to study the causes of Bloody Monday and the lessons learned.

THE DAY LOUISVILLE BURNED

This rising tide of nationalism led to the formation of a political party called the Know-Nothings, so named because of its secretive agenda. It was an offshoot of the defunct Whig party. A hallmark of the Known-Nothings, also known as the American Party, was an intolerance for Catholicism, in part because of a fear the Vatican was attempting to take over the country.For example, the downtown construction of the Cathedral of the Assumption, which opened in 1852 and St. Martin of Tours, constructed in 1854, was seen as proof of such a threat, helping to stoke the paranoia further. This rising sentiment was in part fueled by newspapers that sided with the Know-Nothings, most notably an editor for the Louisville Daily Journal named George D. Prentice, who would ultimately play a key role in Bloody Monday.

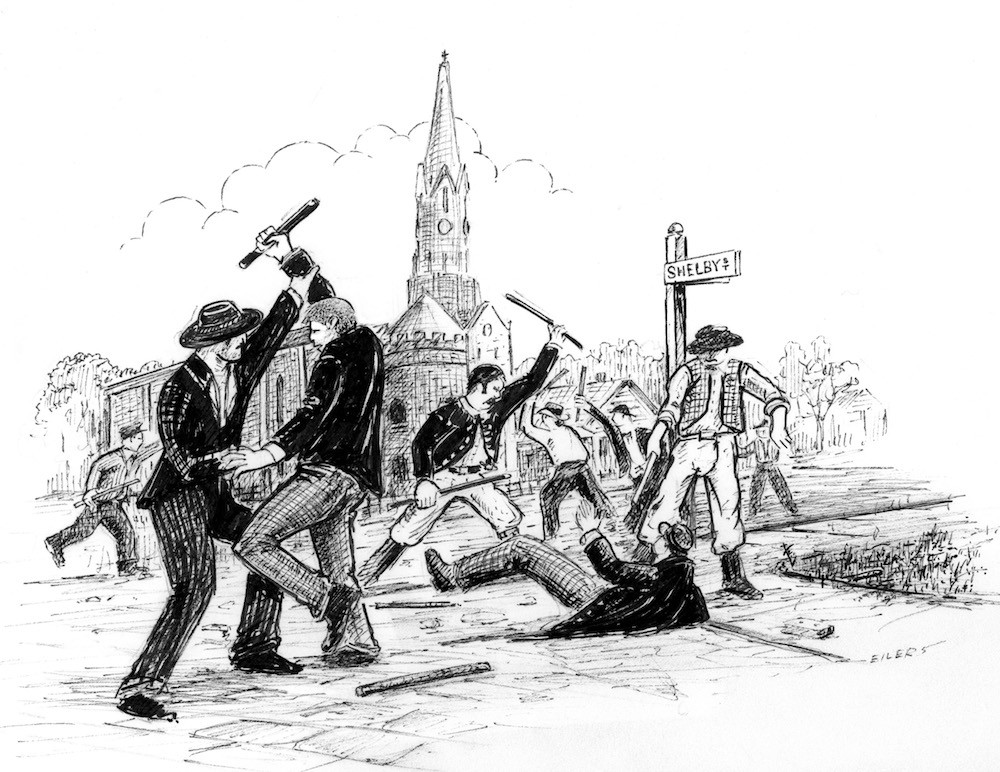

Fearing the rising tide of Catholic immigrants would wrest political control of the city — voter fraud was suspected — the Know-Nothings hatched a plan to keep the immigrants from voting on Election Day. Hired men lined up on either side of the polls, and Know-Nothings with preferred voting interests were given a coded phrase to gain entry. Those without the proper code were not only turned away, they were bullied by hired thugs. Anyone who protested was beaten. From there, the violence escalated.

One account in the Journal described a scene from the sixth voting ward, where two “foreigners” were “forced to run a gauntlet, beat unmercifully, stoned and stabbed.” A former politician, William Thomasson, tried to intervene and calm the crowd, but he was attacked from behind and similarly beaten.

“His gray hairs, his long public service, his manly presence and his thorough [Americanism], availed nothing with the crazed mob,” the Journal wrote.

On and off all day, more than 100 homes and businesses were attacked, looted. A mob destroyed Armbruster’s Brewery, located at Liberty Street and Baxter Avenue and attempted to burn down Green Street Brewery, which was owned by German immigrant Adolph Peter. When the attempt failed, the rioters simply raided the contents and distributed the beer amongst themselves. Mobs along Shelby Street pillaged German businesses and the Journal reported that “fourteen or fifteen men were shot,” including a police officer and “two or three” were killed.

Believing Catholics in the city were collecting and storing weaponry for an uprising, at about 4 p.m., a mob armed with muskets, rifles and cannons marched to St. Martin of Tours on Shelby Street with the intent of attacking it, but it was locked tight. The Cathedral of the Assumption and other Catholic churches were ransacked and threatened with destruction. Louisville Mayor John Barbee, a Know-Nothing himself, was credited with stopping the mobs from destroying the Cathedral of Assumption and others. (Interestingly, bullet holes discovered a little over a decade ago in the steeple of St. Martin are speculated by some to be damage from Bloody Monday.)

Later in the day, near St. Patrick’s Church, three Irishmen were walking on West Main Street near 11th Street and were attacked. Residents of Quinn’s Row retaliated, firing from their windows at the attackers with rifles. By dusk, these frame houses, owned by Irishman Peter Quinn and housing mostly Irish Catholics, were set on fire and people indiscriminately murdered as they tried to escape the blaze.

Quinn himself ran out of his home, on fire and was then beaten and thrown back into his home to burn. The unnamed Irish woman and child were among those injured there. Five men were reported as having been “roasted to death.”

By 1 a.m., newspaper offices had been attacked but ultimately spared major damage, and the drunken throng had settled, leaving blood in the streets and a blazing fire illuminating the downtown skyline. When the bloodshed finally ended, weapons and bodies of the dead were taken to Jefferson County Courthouse (now Louisville Metro Hall).

In the following day’s edition, the Journal decried the violence, saying, “Upon the proceedings of yesterday and last night we have no time, nor heart now to comment. We are sickened with the very thought of the men murdered and houses burned and pillaged, that signalized the American victory yesterday. Not less than twenty corpses from the trophies of the wonderful achievement.”

The news spread quickly around the region. Headlines were alarming, with such exclamations as “Horrible atrocities on women and children!!” and “The city set on fire!!” While it wasn’t the first Know-Nothing riot in America, it was the deadliest and it was a black eye on the city that would linger for some time to come.

BLAME THE PRESS?

Newspapers were different then, said UofL lecturer Leslie Harper, who authored “Lethal Language: The Rhetoric of George Prentice and Louisville’s Bloody Monday” for the journal, Ohio Valley History.Harper points out that the goals for many newspapers in the 19th century were selling product and forwarding an agenda, meaning that often certain editors or publications would align with a political party, movement or cause to capture an audience.

George Prentice did just that, latching onto the Know-Nothing Party a few weeks or months before the Aug. 6 election and writing editorials that called for action against the rising threat of Catholic immigrants. The nation was awash in fear that the Vatican was engineering a dastardly plot to take over America and steal Americans’ liberties, going so far as to tamper with American elections and ultimately undermining the way of life that had been established three generations earlier. The city was primed for an eruption.

Prentice’s practice of using military imagery in what he professed to be harmless metaphors helped contribute to the rising fervor. He warned of looming violence by the immigrants, painting pictures of them as being animals and issuing warnings such as, “we need not and we will not hesitate to speak of the hatred and the insane rage ... in the minds of the mass of the Germans and Irish in this city against the American party.”

His calls for defense included language like, “buckle on your armor” and “strike a glorious blow for our glorious Republic,” while calling the Know-Nothings “soldiers of American liberty,” On Election Day, he wrote, “Americans, are you ready? We think we hear you shout ‘Ready!’ Well, fire! And may heaven have mercy on the foe.”

The result was the confirmed killing of 22 people, but the number is believed by many historians to be as high as 100. The question that persists even today is, how much is Prentice truly to blame?

“There was already a Know-Nothing chapter in Louisville,” Harper said. “There had already been mob violence in Kentucky against Immigrants. He isn’t the sole cause, but I think his rhetoric pushed people over the edge. He excused people for doing anything violent against them by saying they [the immigrants] are going to be violent and they are going to take over the polling places.”

While the press has evolved into the pursuit of fact-based reporting and impartiality, cable news sources and their 24-hour news cycles are viewed as catering on various levels to split factions on the left and on the right. Thinly-veiled calls for riot and revolt, however, aren’t the norm, even if the reporting and commentary can oftentimes be slanted.

Newspapers such as the Louisville Democrat and the Louisville Anzeiger, a German newspaper that was printed in the German language, of course, sided with the Catholics as being victims. The Journal — and the city, given that the Know-Nothing candidates obviously won the election — blamed the immigrants for the escalation of violence on Bloody Monday. No one was ever charged with a crime.

Historians don’t argue that the Irish and German Catholics fought back, but the casualties were overwhelmingly those of the immigrants and eyewitness accounts report gangs of Know-Nothings beating and killing outnumbered immigrants, rather than gang-on-gang or one-on-one tussles.

It may never be known who drew first blood.

Prentice’s words are usually blamed for providing the spark that caused the eruption, but a lack of voting polls in the city, poor planning and poor security all played roles that day, especially given that the warning signs were in full view, including hints of unrest leading up to Aug. 6, such as minor conflicts at the polls that spring.

Frank Towers, an associate history professor at UofL, said the anti-immigration sentiment of the time was to blame more than was Prentice. He points out that many other cities also were sites of Know-Nothing riots in the mid-1850s: St. Louis, Cincinnati, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Orleans, San Francisco and a few smaller cities.

“To me, Prentice seems like other media exhorters in American history,” Towers said. “He did the equivalent of crying ‘fire’ in a crowded theater, but didn’t actually build the unsafe structure, throw the match, nor did he stampede over other members of the crowd.”

“Or, to use a present-day analogy, the U.S. has always had a problem with neo-Nazi fringe groups and self-interested promoters like Richard Spencer, but they wouldn’t have gotten national attention at Charlottesville last year without the current political context.”

Others agree.

“I don’t think he ought to be fingered as the cause of the Bloody Monday riots, as the major voice of incitement,” Tom Owen, UofL historian and former Metro Council member, said of Prentice. “Clearly, he said some very hateful things but ... He wasn’t the only voice in the crowd by a long, long shot.

“The role of Prentice and the causation of the Bloody Monday riots is an issue that has been debated for the last 50 years among Louisville historians. It’s one of the few issues about which there is an ongoing debate.”

Mike McCormack is the national historian for the Ancient Order of Hibernians and he believes Prentice went too far, but did so unintentionally.

“I believe he was just throwing another log on an existing fire,” McCormack said. “Once he threw that log, he said, ‘Holy crap, I didn’t know what this was going to lead to.’ He was going along, riding the high horse and all the sudden he’s, like, ‘What have I done?’”

The Weekly Indiana Sentinel wasn’t so diplomatic in the days after the attack, writing, “By some inscrutable permission of Providence, Prentice is allowed to live and the Louisville Journal to exist, when just the vengeance of God should have sent fire from Heaven to consume the establishment and its infernal editor.”

For his part, Prentice continued to publish the Journal, which later merged with the Louisville Courier. He briefly worked at The Courier-Journal, as a well as finding success as a biographer and poet, before his death in 1870. A statue was commissioned in his honor in 1875 and was located in front of the newspaper until being moved to York Street, outside of the Louisville Free Public Library downtown. In February, the statue and one of John B. Castleman, a onetime Confederate soldier, were vandalized with orange paint by protesters who want them removed because of what they represent. And on Wednesday, Mayor Greg Fischer said he has decided to move the two statues because “Louisville must not maintain statues that serve as validating symbols for racist or bigoted ideology.”

WILL HISTORY REPEAT?

Anti-immigrant sentiments today in America seem prevalent, even some 160 years later, and there are parallels to the Know-Nothings in terms of fears of losing a certain way of life and the perceived freedom Americans enjoy.The Louisville we see today seems mostly evolved from the Louisville in the days of Bloody Monday — the city now is home to private agencies that help immigrants, such as Kentucky Refugee Ministries and Catholic Charities of Louisville, while the city also maintains an Office for Globalization, which says its aim is to tie immigrants and refugees to governmental and non-governmental resources. The annual Festival of Faiths is another example of Louisville’s welcoming community.

Mayor Greg Fischer signed a resolution in 2011 to a long-term campaign called Compassionate Louisville (although he has been sharply criticized for refusing to declare Louisville a sanctuary city, and for a police department that was working too closely with Immigration and Customs Enforcement).

So, how much is the 21st Century Louisville informed by that of 1855?

Owen remembers when the 100th anniversary of the riots were observed in the city in 1955, and there were calls then about removing the Prentice statue because of his role in Bloody Monday. Louisville hadn’t forgotten. But, Owen noted, by 1955, Louisville’s population had, at least from a religious aspect, mostly melded into one, with Protestants and Catholics holding roughly equal numbers. This, he said, is important to the city’s evolution from Bloody Monday.

“That makes us unique,” he said. “Do I think there could be a collective memory of the always-present potential for violence and hatred? Ehhh, not much of one, but perhaps some. Maybe. None of this is simple, to say the least.”

“You cannot bury history,” McCormack said. “What you can do is say, ‘This is what happened when bad elements tried to take over our city, but we defeated them.’ It’s history; to bury it does a great disservice to those who were killed. Louisville defeated that prejudice. [Peter] Quinn came running out of his house with his hair on fire and they beat the shit out of him and threw him back into the fire. That’s not Louisville.” •